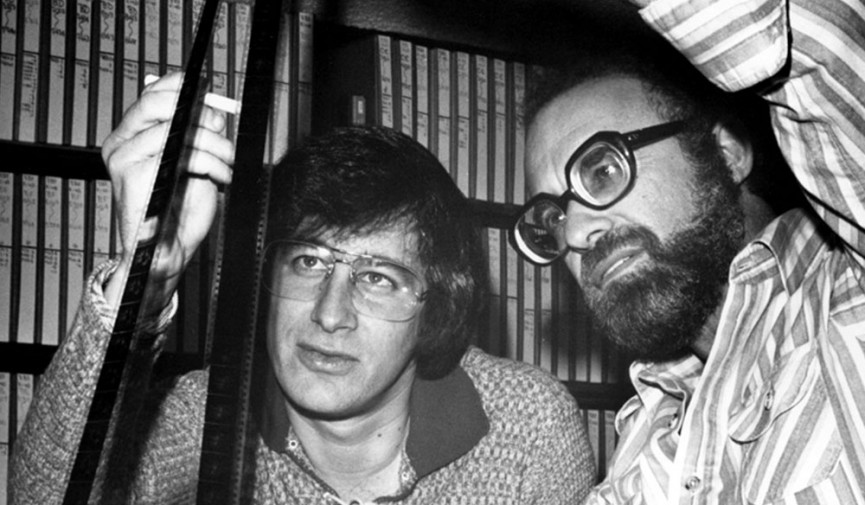

John Cassavetes and Gena Rowlands reviewing footage in their home garage in Hollywood. I wish I could accurately pin down the date of this picture to identify what film they're working on, but the internet provides conflicting information.

“I tell the director before I start, “If you want me to be innovative, give me the chance to make mistakes and maybe we can do something interesting.”… You can play safe and leave it all in, and you sit with the director and say, “Let’s trim here, let’s trim there,” but why not give the director a challenge? That’s what’s nice about film editing: there are a lot of little discoveries you make along the trip, and you put them in. If I find an interesting wrinkle, something different that might work, I say, “If I do it the way the director wants, he’ll never see this interesting little wrinkle.” I’m not doing my job unless I’m giving him options. That’s the key to this business.”

Michael Kahn Interview from Selected Takes: Film Editors on Editing by Vincent LoBrutto

William Friedkin recounts a tale of how he handled studio notes on Sorcerer. This must have been an uncomfortable lunch for the editorial team:

"[Barry] Diller asked if he and [Sid] Sheinberg could see me the next day to pass along a few notes from their team. Since The French Connection experience I wasn’t keen on notes from executives. So I said okay, but I’d want to bring my editors and the writer so they could hear the notes firsthand. Diller and Sheinberg weren’t used to meeting with “below-the-title” guys, but they reluctantly agreed, thinking it was in the spirit of cooperation. It was a sham.

I told Wally [Walon Green, Screenwriter] and Bud [Smith, Editor] and the assistant editors, Jere Huggins and Ned Humphreys, to come unshaven, button their shirts incorrectly, leaving them outside their trousers, wear scruffy, mismatched shoes and socks, and generally look like homeless guys. I told them to wear sullen expressions, project indifference, not smile or nod or do anything that showed understanding, let alone agreement with whatever the executives said—just stare blankly at them while they talked. And don’t react to anything I might say or do, I added. Sheinberg and Diller were successful, high-powered executives, but I felt they had little to offer on how to improve a film I worked on for over a year. I thought that an audience’s response was worth a thousand times more than any executive’s, and that all these guys wanted to do was leave their mark on the film, like a dog pissing on a tree.

The meeting took place over lunch at the posh private dining room at Universal. Sheinberg and Diller were in suits and ties, and my guys were dressed as I had instructed them. Two waiters. Drink orders. Everyone ordered iced tea or bottled water or Diet Coke except me. I asked for a bottle of Smirnoff vodka, no glass. Shocked glances all around, especially from the waiters, who thought I was kidding. I wasn’t. When drinks arrived, I opened the vodka bottle and started glugging. Though not a drinker, I can handle booze and have only been drunk twice in my life. Diller and Sheinberg had a handful of meaningless notes, to which we gave neither visual nor verbal response. Lunch was ordered, but when it arrived, I just kept drinking from the bottle. After about fifteen minutes I fell to the floor facedown. No one reacted, so I just lay there until gradually there was silence. Then Diller turned to Wally and the editors and asked, “Does this happen often?”

“Every day,” Wally deadpanned.

I leave it to you to evaluate this incident. Some of you may find it appalling, others stupid, still others insulting and self-destructive. It was certainly all of that, but at the time, that was my nature. I was still the class clown, and it was also a dumb-ass way of coping with criticism. I wouldn’t want to be treated that way myself."

From William Friedkin's “The Friedkin Connection”

An apparently unusual aspect to Hitchcock’s work method was his entrusting the viewing of dailies to editor George Tomasini and script supervisor Marshall Schlom. “He never went to look at this film,” Schlom asserted. “After dailies, George and I had to come back and tell him what we thought was right or wrong. He knew what he had.” Tomasini, having worked on The Wrong Man, Vertigo, and North by Northwest, was one of the handful of collaborators in whose taste and instincts Hitchcock placed implicit confidence. That track record notwithstanding, Tomasini was only paid $11,000 to edit Psycho.

From "Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of Psycho” by Stephen Rebello

"I really enjoy editing the most... It’s the part I have the most control over, it’s the part I can deal with easiest. I can sit in my editing room and figure it out. I can solve problems that can’t get solved any other way. It always comes down to that in the end. It’s the part I rely on the most to save things, for better or worse. Everybody has their ace in the hole—mine’s editing."

From “The Making of Star Wars” by J.W. Rizler.

One of the highlights from Criterion’s deluxe treatment of Blow Out is an hour long conversation between Brian De Palma and Noah Baumbach, filmed in October of 2010. Noah Baumbach isn’t the first filmmaker that springs to mind when thinking of appropriate De Palma pairings, but it’s fast apparent that he’s a genuine fan [he’s since curated a De Palma Suspense season at New York’s BAMCinématek.]

It’s always enjoyable listening to De Palma rail against conventions, clichés and trends, and this was no exception:

"When you start a movie with a helicopter shot of New York, is this an idea? Oh, we’re in Manhattan. Or these boring drive-ups, where the whole opening of the movie is a car driving up to a building. This is not an idea. Especially in the beginning of a movie where an audience is ready for anything. To waste that time with some boring geography shot mystifies me.

I’m always trying to figure out where the camera is in relation to the material. I’m always saying — and have been saying for years — that the position of the camera is just as important as what you’re photographing. A dirty word to me is coverage. Two shot. Over the shoulder. Stuff you see all the time that just drives me crazy because this, to me, is not directing. You have to think about where the camera is in relationship to the material."

The first time I saw De Palma interviewed was in 1998 when he sat down with Mark Cousins for the BBC’s Scene by Scene movie series. There he openly complained about modern movies, their lack of craft, the absence of cinema. He grumbled about the publicity machine and the lure of celebrity. He even stated that he’d never have agreed to the interview unless he was promoting a film [in this case it was Snake Eyes.] While the latter may be true for most directors and actors who are appearing on the television circuit, it’s rare for them to actually admit it. I managed to source an online version of the interview and re-watch it. Essential viewing, if only to watch De Palma squirm at Cousins’ verbose over-analysis and inappropriate moments of honesty. At one point, Cousins actually states, “[There’s] a sort of maverick quality in some of your work. Not all of it. I think you’ve made some terrible films. I hope it’s okay to say that.”

De Palma makes numerous memorable appearances throughout J.W. Rinzler's excellent book, "The Making of Star Wars". His reaction after George Lucas screened an early cut of the movie:

“What’s all this Force shit?! Where’s all the blood when they shoot people?”

Perhaps the definitive source for tales of De Palma is Julie Salamon’s The Devil’s Candy, a no-holds-barred look at the making of The Bonfire of the Vanities. One of the most memorable moments in the book is when 2nd Unit Director Eric Schwab requests to shoot an establishing shot from the script — “The sky is a labyrinth of planes taking off and landing.” De Palma stated that the day he included the clichéd shot of an airplane landing in one of his movies was the day that he retired. A $100 bet was placed and Schwab began a 6 month process of attempting to film the perfect airplane landing with preparation that involved pinpointing the exact moment that the sun would align with the Empire State Building as Concorde landed on a runway.

Finally, a Blow Out related tale of brat pack rivalry as told by Quentin Tarantino: